Dorks of Black History: Jessie Redmon Fauset

Known as the “Midwife of African American Literature”, Jessie Redmon Fauset was one of the most well-received figures of the Harlem Renaissance movement,

helping birth the literary ambitions of many celebrated Black poets and authors. She was also one of the first authors to represent Black, middle class characters in fiction.

In 1882, Redmon and Annie Seamon Fauset welcomed their seventh child, Jessie Redmon Fauset. Marginally affluent and cultured, Fauset’s father was a successful Presbyterian minister hailing from Old-Line Philadelphia. Despite losing her mother during childhood, Fauset excelled academically, attending the Philadelphia High School for Girls and holding the title as their first Black graduate.

With a scholarship to Cornell University, Fauset went on to study Classical Languages and is rumored to have been the first African American inducted into the Phi Beta Kappa Society. After graduating from Cornell in 1905, she earned her Masters degree in French at the University of Pennsylvania.

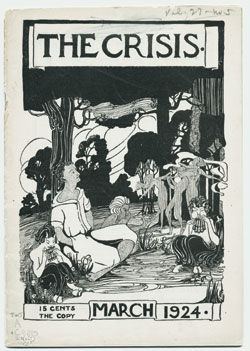

Following graduation Fauset taught Latin and French in Washington D.C and spent her summers studying at la Sorbonne in Paris. In 1919, Fauset left la Sorbonne to work under W.E.B DuBois as the literary editor for The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP. In addition to contributing regularly to the magazine, Fauset also fostered notable literary figures and was the first person to publish Langston Hughes’ work. She was known for hosting gatherings at her house where the brightest minds of the time would congregate to discuss literature, read poetry aloud and converse in French.

Fauset also edited The Brownie Book, an NAACP publication geared towards Black children. Fauset’s personal contributions to The Crisis often detailed her extensive travels and biographies of prominent Black figures. In 1926, Fauset left her position after ongoing conflict between W.E.B DuBois and herself.

T.S Stribling’s novel Birthright served as a catalyst to Fauset’s fiction career, written by a white man, she felt the novel inaccurately depicted Black culture and that such stories should be written by Black authors. Between 1924 and 1933, Fauset published four novels: There Is Confusion (1924), Plum Bun: A Novel Without A Moral

, (1928), The Chinaberry Tree: A Novel of American Life

, (1931), and Comedy: American Style

(1933). Fauset’s novels primarily examined the lives of upper-middle class African Americans, with the intention of showing younger readers what they were capable of.

Fauset married insurance broker Herbert Harris in 1929 at the age of 47. They remained together until Harris passed in 1958. At that time Redmon moved back to Philadelphia with her brother where she would stay until her death in 1961.

Fauset’s time at The Crisis is overwhelmingly considered the most prolific literary period during the magazine’s 104-year run. In his biography The Big Sea, Langston Hughes would mention Fauset, saying, “Jessie Fauset at The Crisis, Charles Johnson at Opportunity, and Alain Locke in Washington were the people who midwifed the so-called New Negro Literature into being. Kind and critical — but not too critical for the young — they nursed us along until our books were born.”

As one of the founding members of the Harlem Renaissance and a mentor to some of the greatest names in African American Modernist Literature, Jessie Redmon Fauset can confidently wear the title as one of the most influential Dorks of Black History.

In closing, I leave you with Fauset’s La Vie C’est la Vie, a poem with a subject we should all be familiar with: unrequited love.

La Vie C’est la Vie

On summer afternoons I sit

Quiescent by you in the park,

And idly watch the sunbeams gild

And tint the ash-trees’ bark.

Or else I watch the squirrels frisk

And chaffer in the grassy lane;

And all the while I mark your voice

Breaking with love and pain.

I know a woman who would give

Her chance of heaven to take my place;

To see the love-light in your eyes,

The love-glow on your face!

And there’s a man whose lightest word

Can set my chilly blood afire;

Fulfillment of his least behest

Defines my life’s desire.

But he will none of me, nor I

Of you. Nor you of her. ‘Tis said

The world is full of jests like these–

I wish that I were dead.

Categories: Feature