The Grieving Process: Six Months Later

Reflections on the stages of grief and personal progression through the grieving process since the loss of a close friend six months ago.

Month One:

It’s approximately 11:45pm when I get the call. I’m exchanging goodnights with my then-boyfriend when, seeing an unfamiliar number flash across my screen, I automatically press ignore. Still, deep down in the bottomless well of my stomach, I know.

Almost immediately, the number calls again. This time I click over and answer.

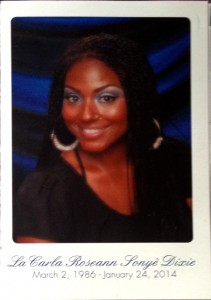

My friend LaCarla’s brother greets my hello with a choked, “Danielle? Carla’s dead.”

As cliché as it may sound, the room seems to spin out of focus for a moment. Stunned, we swap intermittent Wow’s and I can’t believe it’s to cut through the silence of that truth. A few minutes later, LaCarla’s mother calls and I switch lines again.

For some reason, I feel I have to be strong for her mother. I comfort her and ask practical questions, I promise to take care of tedious details, even though she is with LaCarla, or her body as it is, in Indiana, and I am in California.

After a final call to LaCarla’s younger sister, who is suffering through winter exams at San Diego State, I call my mother. Finally, I think.

Her voice is thick and coated with sleep when she picks up the phone. “Hello?”

“Mooooom–” My response is an embarrassing, guttural wail.

“What?” Now frantic.

“Carla – died,” I sob like a six-year-old, chest heaving.

A sigh. Then, in a patient, soothing voice, “But Danielle, you knew…”

I like to think she said those things in comfort. I can’t much remember them now anyway.

My voice is unwavering when I bite back, “I know that she was sick, I knew that this was going to happen, but she was my best friend–,” A deep breath, “– Like a sister to me, and I am allowed to be upset, I am allowed to be sad. Okay?”

Of course she understands. She lets me cry. Afterwards, I fall into a deep, dreamless sleep.

At some point during those conversations, I turned 28. Which means that because she was in Indiana, which is on Eastern Standard Time, LaCarla died in the early hours of my date of birth.

Month Two:

The day after my birthday I receive news that I’ve successfully booked a location for my website launch party. I am given the choice of a quickly approaching Saturday, or a more reasonable date towards the end of February. Of course I choose the former, delighting in a distraction, something to pour myself into that will give denial an extended deadline.

For the most part, it’s easy to pretend like it didn’t happen, like LaCarla isn’t dead. In my day-to-day, real life, no one knows LaCarla. If they do, they know her as my long distance, cancer-sick friend, and assume terminal illness makes death easier to deal with, expected somehow.

In fact, once a person has successfully gone to battle with cancer several times over several years, you begin to forget that death is an option. Cancer just becomes this thing that flares up for them every once in a while. Every time they beat it you think they’ve beat it for good, but whenever it comes back you never consider that maybe it’s back for good.

My then-therapist tells me that a “typical” grieving period lasts 90 days. She means to comfort, but I panic instead. Right then, consuming grief is the only way I know how to be close to her. On the outside I probably look like a slightly more tense version of myself, a little brittle around the edges, but for the most part holding it together. Still, I can hardly tell you anything that happens during that second month after she’s gone. People fade into the walls and their voices become garbled and distant, adults in a Charlie Brown cartoon.

Month Three:

Like a mantra, on the morning of LaCarla’s birthday and memorial service I repeat to myself, “Don’t cry, don’t cry, don’t cry.”

I’m not against crying, per se. I’ve done it a handful of times — not enough — since it happened. At this point, I fear I resemble a spigot that’s been wrenched too tight, threatening to burst. I resolve not to burst that day.

I say a few words at her memorial, words I don’t memorize beforehand that are quickly forgotten, words that are true, but do not threaten my shaky surface. Other friends and family allow their facades to crumble, and take moments, sometimes longer, to compose themselves and steady their handwritten eulogies before reading more heartfelt words. I am ashamed.

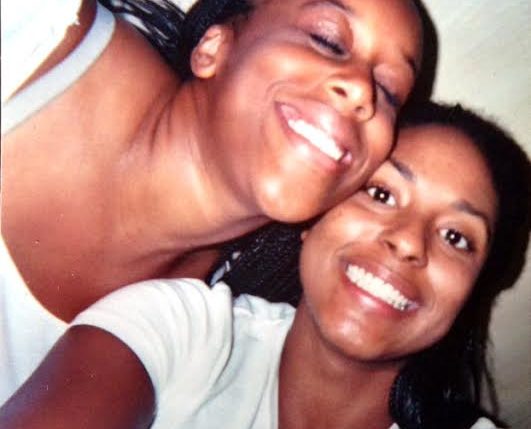

I’m afraid if I put into words what LaCarla means to me that I’ll lose something else, that she’ll move further away from being a person and closer to becoming a memory.

Everyone closes their speeches on a positive, hopeful note, declaring knowledge that LaCarla is in heaven, and won’t our eventual reunion be a joyous, blessed day? Lacking their assurance I wonder, am I allowed to be upset that she’s not with me here, right now?

Month Four:

For the first time, my dad talks to me about the death of his mother, which occurred when he was 19-years-old and serving at the March Air Force Base in Perris, California, half a country away from the rest of his family in Cleveland, Ohio.

He talks about how it was different for his siblings, who saw his mother every day and felt the loss more immediately. With college and work demanding most of his attention in California, he was in touch as often as any good son would be, a few times a month, weekly.

Without thinking I chime in, “It took longer for me too, a couple weeks had passed before I found myself thinking, maybe I would have called her by now.”

He nods slowly, sadly.

I wonder about some of the people I introduced LaCarla to, people I no longer talk to. It bothers me that they don’t know that she’s passed, makes her feel less real somehow. I have an urge to call up my former co-worker, my ex-boyfriend’s friend with whom she shared a brief flirtation, and tell them the entire story. I just need them to know.

Month Five:

I get something like a second wind. It’s as though a mesh film has been lifted from my view, and things begin to look a little brighter, vibrant. I won’t pretend to postulate what LaCarla would have wanted, but I recognize that spending my evenings and weekends wasting away in a dreary apartment is no way to honor her life, which was lived with courage, resilience, and unfaltering faith.

Since she was first diagnosed, and through numerous cancer treatments, LaCarla remained hopeful and diligent, first attaining her cosmetology license before moving to Indiana to further her education as an esthetician. It had seemed like a cruel joke when she called me last May to tell me they’d found cancerous lesions in her lungs just weeks before her esthetician classes were scheduled to begin.

When I last saw her in December, she mentioned traveling somewhere tropical when it was all over. “Where should we go?” she asked me.

Sometimes I wish I had let her be more vulnerable with me, express her fears about the future, her anger towards her body and the cells that had betrayed her, when she had every right to be a perfectly healthy 20-something adult, just like me. I want to assure her that everyone who says things happen for a reason, every person who claims this as part of some higher being’s plan, is undoubtedly wrong. There was never any reason for her suffering.

I learn that you don’t ever get closure from those regrets, the things you wish you’d said. If you’re smart, you say them to the people who are still with you, even when it’s uncomfortable and hard, even when it hurts. Regardless of how the conversations unfold, there’s some relief in knowing you tried.

Month Six:

One thing I said to my mother on the night of LaCarla’s passing was that it had happened practically on my birthday, that every birthday from then on would be ruined because I would be reminded of her death. My mom, still drowsy, but trying her best to comfort had said, “No, honey, that’s why she chose to pass before your actual birthday, she knew…”

Of course, I found out the next day that she actually had died in the early hours of January 24th, very close to the time of my birth, as a matter of fact. I still think my mother was right though; I think LaCarla chose that time on purpose, I think she knew.

Now, it seems almost appropriate to celebrate her on a day that congratulates me on living, a task I’m well aware is not as easy for some. The knowledge that we are forever linked through these contradicting and dramatic life events no longer terrifies me, nor does the fact that on my birthday, probably every year for the rest of my life, my mind will be consumed with thoughts of her, some joyous, others mournful.

In the past few years my birthday has become a predictable, anti-climactic event, but now I find myself looking forward to doing things she would have enjoyed, things we’d intended to do together. In the coming years I plan to spend my birthday lounging on tropical shores while sipping cocktails from a coconut, at a secluded weekend retreat in the Palm Desert, staying up all night dancing at an underground Berlin nightclub.

I don’t think the grieving process ever really ends, per se. What changes is how you feel in your grief, the effect it has on your mood and productivity. Lately, when I find myself pining for her, that moment no longer extends for a week, or two. It’s replaced with a feeling closer to nostalgia, a twinge of gratefulness and acknowledgment that the love we share is eternal. It will continue to exist in the hallway mazes of our alma mater, the brick walls that hold my childhood living room, the Indianapolis Airport, where we embraced in our last formal goodbye.

Categories: Blog