Dorks of Black History: Jelly Roll Morton

In honor of Black History Month, I am introducing a brief series of articles recognizing the Dorks of Black history, specifically those who were influential in music or literature.

First up is Jelly Roll Morton, a Creole musician who lauded himself the “Inventor of Jazz” and is credited in history as the first great jazz composer and pianist. It’s difficult to imagine a time before jazz, but Jelly Roll’s travels between New Orleans, St. Louis, Chicago and Harlem in the early 20th century allowed him to meld ragtime, blues, and negro spirituals to form a new genre.

Though he was given the name Ferdinand Joseph LaMonte at birth, on which date remains unclear. Most jazz scholars believe the musician was born in 1890, but Jelly Roll was known to be such a storyteller that many facts concerning his legacy are still debated. It is believed that he claimed his birthday to be in 1885 to appear more reputable as a young musician.

Jelly Roll was born to a Haitian father and Creole mother in New Orleans, Louisiana. His father deserted them when he was a young child and his mother eventually remarried a man with the last name Mouton. Ferdinand took his stepfather’s name and Anglicized it to Morton.

Morton showed musical promise early on and began experimenting with trombone around age six. He took guitar lessons from a Spanish man in his neighborhood and quickly moved onto drums and violin. He put off learning piano until he was 10, afraid the instrument would brand him a “sissy.”

After Jelly Roll’s mother died in 1906, he went to live with his grandmother, Mimi Pechet and began playing in brothels as a pianist. It was there he coined the stage name “Jelly Roll”, which at the time was slang for female genitals. Jelly Roll told his grandmother he was working nights at a barrel factory and when she found out about his real occupation, she promptly threw him out.

Branded a disgrace and forbidden from returning home, Jelly Roll briefly moved in with his Godmother in Biloxi, Mississippi. He played piano at local clubs for a little while, but was soon chased out of town by a lynch mob following rumors that he’d been involved with a white club owner’s daughter.

For a while, Jelly Roll traveled the south, performing as a solo pianist and in various minstrel shows. He was also an avid gambler, pool shark and occasional pimp; these hobbies allowed him to dress the part of the successful musician and helped sell his lofty fabrications. He had a flamboyant style and sported a gold front tooth with a diamond insert.

In defense of his arrogance, Jelly Roll was a standout musician and composer. He had a unique left hand bass line piano style that mimicked the sounds of an ensemble with melody, harmonic support and rhythmic punctuations that gave a sense of multiple instruments operating collectively. This aspect of Jelly Roll’s music was a pervasive quality in much of the early jazz tradition in New Orleans.

Jelly Roll continued traveling the south and midwest and around 1917, began publishing original music, including “Jelly Roll Blues.” During this upswing in his career, Jelly Roll relocated to California with bandleader Bill Johnson and his sister Anita Gonzalez (Mama ‘Nita). He opened a club with Mama ‘Nita in Los Angeles called The Jupiter and quickly earned a reputation for some of the liveliest entertainment in town. Unfortunately, The Jupiter’s success was short lived and they were forced to close after competitors reported them to the police for suspicious activity.

Jelly Roll spent a few years traveling between Los Angeles and San Francisco before moving back to Chicago in 1923. There he began a working skiffle band using a jug, kazoo and suitcase as instruments. During this time he released one of his most celebrated tracks, “Wolverine Blues.” Jelly Roll also recorded a series of solo piano performances for Gennett record label that have since been recognized as some of the most influential early jazz recordings.

These years in Chicago were good to Jelly Roll and during them he compiled more of his arrangements of original compositions, popular selections like “Black Bottom Stomp”, “Beale Street Blues”, “The Chant”, “Doctor Jazz”, “The Peals” and “Grandpa’s Spells.”

In 1926, he was chosen to lead Victor Talking Machine Company’s studio band The Red Hot Peppers. The band’s rotation of musicians over the next two years included some of the top artists of the era, including trombonist Kid Ory, clarinetists Omer Simeon, Barney Bigard and Johnny Dodds, banjoist Johnny St. Cyr and drummer Baby Dodds.

In 1928 Jelly Roll moved to New York following his marriage to showgirl Mabel Bertrand. He led a New York version of The Red Hot Peppers which also bragged an impressive rotating lineup including ‘gut-bucket’ trumpeter Bubber Miley, drummer Zutty Singleton, and bassist Pops Foster. For the most part, the early to mid 1920s were considered Jelly Roll’s career zenith and by the time he returned to Harlem, much of his new material was considered outdated by the renaissance crowd. The New York reboot of The Red Hot Peppers dismantled within a year and Jelly Roll was denied entrance into the ASCAP (American Society of Composeers, Authors and Publishers) as well as the The American Federation of Musicians Union.

Jelly Roll moved to Washington DC in 1935 where he managed and performed at The Jungle Inn nightclub. There he collaborated with pioneering researcher Alan Lomax, who was documenting folk life and music for the Library of Congress. Between May 23rd and June 12th in 1938, Lomax recorded Morton’s extemporaneous commentary about his life and career, often punctuated by musical passages at the piano.

Jelly Roll experienced a slight resurgence in popularity in the late 1930’s and briefly returned to New York to record with Sidney Bechet, Albert Nicholas and Sidney DeParis Morton. In 1938 he was stabbed by The Jungle Inn’s owner’s friend. He was declined treatment by a local whites-only hospital and transported to a colored hospital further away, where he was left untreated for several more hours. After this Morton developed asthma and was often ill. He blamed this illness on a voodoo curse cast on him by his Godmother when he was a child.

Jelly Roll moved to California in 1939 where he hoped he’d find some relief in the warm climate. On July 10, 1941, he passed away in Los Angeles. At his funeral no music was played and he was buried in a pauper’s grave. Fellow musicians Kid Ory, Mutt Carey, Fred Washington and Ed Garland were among his pall bearers. It is rumored that Jelly Roll isolated many of his contemporaries with the self-aggrandizing subterfuge he was known for.

Jelly Roll’s stage name is what first stood out to me as a potential dork-identifying feature. I figured anyone who purposely chose such a scandalous name had to have an interesting story behind them. After learning more, I became intrigued by Jelly Roll’s persistent claims of being the inventor of jazz. Given the racial climate at the time, I couldn’t help wondering how true they were and whether he’d ever received the credit he was due.

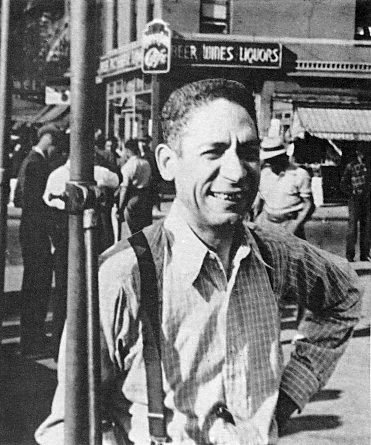

From left to right, “Common Sence” Ross, Albertine Pickins, Ferd “Jelly Roll” Morton, Ada “Bricktop” Smith, Eddie Rucker, Mabel Watts.

Jelly Roll was by no means a saint; he began his career working in brothels and over its 30-year course would nearly go broke losing large sums at horse tracks, at one point even having to sell his diamond tooth insert. He was boastful and arrogant and the exaggerated tales of his legacy are still being untangled by jazz historians.

Aside from the gambling and prostitutes, doesn’t the description of Jelly Roll ring reminiscent of a certain self-proclaimed genius hip hop artist-come-fashion designer? It makes me wonder how we’ll remember our current Black icons, but it also reminds me of an attitude that seems to linger when it comes to Black men recognizing their worth. Humility is a virtue, but an unyielding confidence, especially during times when society seeks to dehumanize and degrade you, is essential to building your own success.

Although most historians and experts agree that Jelly Roll’s presence in early jazz has been downplayed, he has received some post-mortem dues. In the 1990s, his life and musical career became the topic of a Broadway production called Jelly’s Last Jam, starring Gregory Hines. He has been inducted into Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and was elected a charter member of the Gennett Records Walk of Fame. In 2008, Jelly Roll was inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame.

Whether or not he deserves the credit of inventor of jazz will remain up for debate, but there is no doubt that Jelly Roll Morton greatly influenced the genre and remains one of jazz’s most colorful figures.

Look forward to one more Dorks of Black History article and in the meantime, check out the video above of Jelly Roll Morton’s full Library of Congress recordings!

Categories: Feature